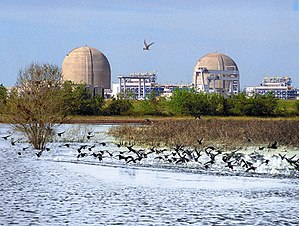

The South Texas Project Electric Generating Station (also known as STP, STPEGS, South Texas Project), is a nuclear power station southwest of Bay City, Texas, United States. STP occupies a 12,200-acre (4,900 ha) site west of the Colorado River about 90 miles (140 km) southwest of Houston. It consists of two Westinghouse Pressurized Water Reactors and is cooled by a 7,000-acre (2,800 ha) reservoir, which eliminates the need for cooling towers.

| South Texas Project (STP) Electric Generating Station | |

|---|---|

South Texas Project, Units 1 & 2 (NRC image) | |

| |

| Official name | South Texas Project Electric Generating Station |

| Country | United States |

| Location | Matagorda County, near Bay City, Texas |

| Coordinates | 28°47′44″N 96°2′56″W / 28.79556°N 96.04889°W |

| Status | Operational |

| Construction began | December 22, 1975 |

| Commission date | Unit 1: August 25, 1988 Unit 2: June 19, 1989 |

| Construction cost | Units 1–2: $12.55 billion (USD 2010) or $17.1 billion in 2023 dollars[1] |

| Owners | Constellation Energy (44%) City of San Antonio (40%) City of Austin (16%) |

| Operator | STP Nuclear Operating Company (STPNOC) |

| Nuclear power station | |

| Reactor type | PWR |

| Reactor supplier | Westinghouse |

| Cooling source | Main Cooling Reservoir (7,000 acres (2,800 ha), up to 202,600 acre-feet (249,900,000 m3) of cooling water storage, filled by pumping water from the Colorado River) |

| Thermal capacity | 2 × 3853 MWth |

| Power generation | |

| Units operational | 2 × 1280 MW |

| Make and model | WH 4-loop (DRYAMB) |

| Units cancelled | 2 × 1350 MW ABWR |

| Nameplate capacity | 2560 MW |

| Capacity factor | 97.16% (Unit 1, 2017-2019) 98.75% (Unit 2, 2017-2019)[2] 85.6% (Unit 1, lifetime)[3] 85.1% (Unit 2, lifetime)[4] |

| Annual net output | 21,920 GWh (2022) |

| External links | |

| Website | www.stpnoc.com |

| Commons | Related media on Commons |

History

edit1971–1994

editOn December 6, 1971, Houston Lighting & Power Co. (HL&P), the City of Austin, the City of San Antonio, and the Central Power and Light Co. (CPL) initiated a feasibility study of constructing a jointly-owned nuclear plant. The initial cost estimate for the plant was $974 million[5] (equivalent to approximately $5,700,741,167 in 2015 dollars[6]).

By mid-1973, HL&P and CPL had chosen Bay City as the site for the project and San Antonio had signed on as a partner in the project. Brown and Root was selected as the architect and construction company. On November 17, 1973 voters in Austin narrowly approved their city's participation[7] and the city signed onto the project on December 1. Austin held several more referendums through the years on whether to stay in the project or not.[8][9][10]

An application for plant construction permits was submitted to the Atomic Energy Commission, now the Nuclear Regulatory Commission (NRC), in May 1974 and the NRC issued the permits on December 22, 1975. Construction started on December 22, 1975.[11]

By 1978, the South Texas Project was two years behind schedule and had substantial cost overruns.[12] A new management team had been put in place by HL&P in late 1978 to deal with the cost overruns, schedule delays and other challenges.[citation needed] However, events at Three Mile Island in March 1979 had a substantial impact on the nuclear industry including STNP.[citation needed] The new team again moved forward with developing a new budget and schedule. Brown and Root revised their completion schedule to June 1989 and the cost estimate to $4.4–$4.8 billion.[citation needed] HL&P executives consulted with its own project manager and concluded that Brown and Root was not making satisfactory progress and a decision was reached to terminate their role as architect/engineer but retain them as constructor.[citation needed] Brown and Root was relieved as architect/engineer in September 1981 and Bechtel Corporation contracted to replace them.[citation needed] Less than two months later, Brown and Root withdrew as the construction contractor and Ebasco Constructors was hired to replace them in February 1982 as constructor.[citation needed]

Austin voters authorized the city council on November 3, 1981 to sell the city's 16 percent interest in the STP.[13] No buyers were found.[citation needed]

Unit 1 reached initial criticality on March 8, 1988 and went into commercial operation on August 25.[14] Unit 2 reached initial criticality on March 12, 1989 and went into commercial operation on June 19.[15]

In February 1993, both units had to be taken offline to resolve issues with the steam-driven auxiliary feedwater pumps. They were not back in service until March (Unit 1) and May (Unit 2) of 1994.[citation needed] The history of STNP is somewhat unusual since most nuclear plants that were in the early stages of engineering construction at the time of the Three Mile Island event were never completed.[citation needed]

2006–present

editOn June 19, 2006, NRG Energy filed a letter of intent with the NRC to build two 1,358-MWe advanced boiling water reactors (ABWRs) at the South Texas Nuclear Project site.[16] South Texas Nuclear Project Partners CPS Energy and Austin Energy were not involved in the initial letter of intent and development plans.[citation needed]

On September 24, 2007, NRG Energy filed an application with the NRC to build two Toshiba ABWRs at the South Texas Nuclear Project site.[16] It was the first application for a nuclear reactor submitted to the NRC since 1979. The proposed expansion would generate an additional 2700 MW of electrical generating capacity, which would double the capacity of the site.[17] The total estimated cost of constructing the two reactors is $10 billion, or $13 billion with financing, according to Steve Bartley, interim general manager at CPS Energy.[citation needed]

In October 2009, main contractor Toshiba had informed CPS Energy that the cost would be "substantially greater," possibly up to $4 billion more. As a result of the escalating cost estimates for units 3 and 4,[18] in 2010 CPS Energy reached an agreement with NRG Energy to reduce CPS's stake in the new units from 50% to 7.625%. To that point, CPS Energy had invested $370 million in the expanded plant. CPS Energy's withdrawal from the project put the expansion into jeopardy.[citation needed]

In October 2010, the South Texas Project announced that the Tokyo Electric Power Company (TEPCO) had entered into an agreement with Nuclear Innovation North America (a joint venture between the reactor manufacturer, Toshiba, and plant partner NRG Energy) which was the largest of the two stakeholders in the proposed reactors, to purchase an initial 9.2375% stake in the expansion for $125 million, and $30 million for an option to purchase an additional stake in the new units for $125 million more (resulting in approximately 18% ownership by TEPCO, or 500 MW of generation capacity). The agreement was made conditional upon STNP securing construction loan guarantees from the United States Department of Energy.[19][20][21]

On 19 April 2011, NRG announced in a conference call with shareholders, that they had decided to abandon the permitting process on the two new units due to the ongoing expense of planning and slow permitting process. Anti-nuclear campaigners alleged that the financial situation of new partner TEPCO, combined with the ongoing Fukushima nuclear accident were also key factors in the decision.[22] NRG has written off its investment of $331 million in the project.[23]

Despite the April 2011 NRG announcement of the reactor's cancellation, the NRC continued the combined licensing process for the new reactors in October 2011.[24] It was unclear at the time why the reactor license application was proceeding. During early 2015 some pre-construction activities were performed on site and initial NRC documents listed the original targeted commercial operational dates as March 2015 for unit 3 and a year later for the other unit.[25] On February 9, 2016 the NRC approved the combined license.[26] Due to market conditions, no construction events occurred at that time. The two planned units do not currently have a planned construction date.[27]

On February 15, 2021 during a major power outage that impacted much of the state of Texas, an automatic reactor trip shut South Texas Nuclear Generation Station Unit 1 due to low steam generator levels. According to a Nuclear Regulatory Commission report, the low steam generator levels were due to loss of feedwater pumps 11 and 13. However, Unit 2 and both units at the Comanche Peak Nuclear Power Plant remained online during the power outage.

Electricity production

editSouth Texas Project Electric Generating Station generated 21,920 GWh in 2022.

| Year | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2001 | 1,886,321 | 1,525,367 | 1,023,965 | 1,693,902 | 1,749,601 | 1,803,826 | 1,862,368 | 1,861,391 | 1,784,413 | 948,097 | 1,821,433 | 1,879,914 | 19,840,598 |

| 2002 | 1,877,631 | 1,694,952 | 1,874,294 | 1,802,364 | 1,853,569 | 1,651,816 | 1,804,722 | 1,863,231 | 1,809,080 | 961,912 | 648,839 | 1,207,192 | 19,049,602 |

| 2003 | 993,000 | 858,234 | 1,167,859 | 906,020 | 926,323 | 897,961 | 924,414 | 1,550,300 | 1,826,511 | 1,901,587 | 1,835,032 | 1,901,300 | 15,688,541 |

| 2004 | 1,794,208 | 1,783,984 | 1,866,066 | 967,940 | 1,898,881 | 1,833,986 | 1,888,035 | 1,886,885 | 1,832,462 | 1,898,705 | 1,846,256 | 1,874,559 | 21,371,967 |

| 2005 | 1,910,104 | 1,425,909 | 1,145,000 | 1,347,849 | 1,899,476 | 1,827,979 | 1,882,165 | 1,865,460 | 1,793,374 | 961,783 | 1,812,505 | 1,917,689 | 19,789,293 |

| 2006 | 1,918,500 | 1,734,226 | 1,916,180 | 1,848,924 | 1,902,066 | 1,835,603 | 1,894,140 | 1,889,118 | 1,754,581 | 949,107 | 1,751,295 | 1,974,529 | 21,368,269 |

| 2007 | 1,978,523 | 1,769,752 | 1,631,719 | 1,020,990 | 1,997,207 | 1,913,083 | 1,974,291 | 1,945,127 | 1,911,186 | 1,994,784 | 1,951,698 | 2,020,923 | 22,109,283 |

| 2008 | 2,027,749 | 1,894,252 | 1,857,380 | 1,059,644 | 1,996,808 | 1,911,071 | 1,970,008 | 1,968,743 | 1,883,018 | 1,091,075 | 1,804,680 | 2,028,321 | 21,492,749 |

| 2009 | 2,026,109 | 1,816,781 | 2,001,913 | 1,933,642 | 1,976,442 | 1,893,260 | 1,945,400 | 1,945,673 | 1,491,904 | 987,917 | 1,314,044 | 2,023,063 | 21,356,148 |

| 2010 | 1,901,689 | 1,616,544 | 1,878,021 | 959,782 | 1,894,264 | 1,905,405 | 1,965,866 | 1,889,669 | 1,908,067 | 2,000,442 | 1,180,689 | 2,026,343 | 21,126,781 |

| 2011 | 2,019,203 | 1,831,865 | 2,010,915 | 1,022,733 | 1,722,511 | 1,919,280 | 1,972,583 | 1,862,971 | 1,922,238 | 1,926,927 | 1,161,050 | 993,620 | 20,365,896 |

| 2012 | 1,000,676 | 932,122 | 954,597 | 1,191,768 | 1,996,956 | 1,916,509 | 1,972,364 | 1,968,957 | 1,917,986 | 1,618,514 | 1,046,510 | 2,027,134 | 18,544,093 |

| 2013 | 1,129,541 | 907,783 | 1,001,457 | 1,214,363 | 1,800,887 | 1,909,913 | 1,972,700 | 1,929,852 | 1,755,607 | 1,457,708 | 1,482,475 | 1,265,570 | 17,827,856 |

| 2014 | 1,996,545 | 1,803,728 | 1,467,789 | 949,590 | 965,031 | 1,819,148 | 1,938,482 | 1,937,255 | 1,886,353 | 1,964,871 | 1,929,852 | 1,993,023 | 20,651,667 |

| 2015 | 1,994,899 | 1,798,046 | 1,876,998 | 944,816 | 1,633,328 | 1,873,563 | 1,924,005 | 1,921,588 | 1,870,805 | 1,474,997 | 931,979 | 1,155,529 | 19,400,553 |

| 2016 | 1,867,890 | 1,853,605 | 1,971,083 | 1,899,518 | 1,791,929 | 1,869,512 | 1,921,476 | 1,921,320 | 1,863,053 | 1,199,327 | 1,551,143 | 1,984,447 | 21,694,303 |

| 2017 | 1,982,755 | 1,781,424 | 1,496,196 | 941,003 | 1,947,349 | 1,872,796 | 1,915,879 | 1,922,021 | 1,874,558 | 1,951,826 | 1,911,553 | 1,984,116 | 21,581,476 |

| 2018 | 1,990,840 | 1,791,895 | 1,716,130 | 1,026,669 | 1,948,056 | 1,862,498 | 1,926,877 | 1,926,702 | 1,862,974 | 1,104,073 | 1,542,275 | 1,988,643 | 20,687,632 |

| 2019 | 1,989,139 | 1,794,419 | 1,977,848 | 1,907,580 | 1,952,400 | 1,865,069 | 1,923,822 | 1,916,348 | 1,861,164 | 1,076,425 | 1,746,675 | 1,982,408 | 21,993,297 |

| 2020 | 1,981,132 | 1,854,898 | 1,386,851 | 1,267,605 | 1,965,407 | 1,887,512 | 1,941,500 | 1,925,033 | 1,879,619 | 1,963,043 | 1,910,507 | 1,995,650 | 21,958,757 |

| 2021 | 1,991,790 | 1,680,259 | 1,600,163 | 1,269,956 | 1,955,134 | 1,730,291 | 1,933,495 | 1,927,320 | 1,879,819 | 1,211,341 | 1,688,551 | 1,986,885 | 20,855,004 |

| 2022 | 1,996,621 | 1,804,682 | 1,990,353 | 1,908,367 | 1,953,488 | 1,870,425 | 1,924,485 | 1,927,102 | 1,859,877 | 1,164,373 | 1,533,211 | 1,986,901 | 21,919,885 |

| 2023 | 1,981,393 | 1,794,205 | 1,496,119 | 1,181,761 | 1,941,365 | 1,862,343 | 1,911,690 | 1,904,511 | 1,853,615 | 1,953,564 | 1,917,848 | 1,988,730 | 21,787,144 |

| 2024 | 1,634,136 | 1,833,846 | 1,517,587 | 913,191 | 1,292,316 |

1985 whistleblowing case

editNuclear whistleblower Ronald J. Goldstein was a supervisor employed by EBASCO, which was a major contractor for the construction of the South Texas plants. In the summer of 1985, Goldstein identified safety problems to SAFETEAM, an internal compliance program established by EBASCO and Houston Lighting, including noncompliance with safety procedures, the failure to issue safety compliance reports, and quality control violations affecting the safety of the plant.[citation needed]

SAFETEAM was promoted as an independent safe haven for employees to voice their safety concerns. The two companies did not inform their employees that they did not believe complaints reported to SAFETEAM had any legal protection. After he filed his report to SAFETEAM, Goldstein was fired. Subsequently, Goldstein filed suit under federal nuclear whistleblower statutes.[citation needed]

The U.S. Department of Labor ruled that his submissions to SAFETEAM were protected and his dismissal was invalid, a finding upheld by Labor Secretary Lynn Martin. The ruling was appealed and overturned by the Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals, which ruled that private programs offered no protection to whistleblowers. After Goldstein lost his case, Congress amended the federal nuclear whistleblower law to provide protection for reports made to internal systems and prevent retaliation against whistleblowers.[29][page needed]

Ownership

editThe STPEGS reactors are operated by the STP Nuclear Operating Company (STPNOC). Ownership is divided among Constellation Energy at 44 percent, San Antonio municipal utility CPS Energy at 40 percent and Austin Energy at 16 percent.[30]

Surrounding population

editThe Nuclear Regulatory Commission defines two emergency planning zones around nuclear power plants: a plume exposure pathway zone with a radius of 10 miles (16 km), concerned primarily with exposure to, and inhalation of, airborne radioactive contamination, and an ingestion pathway zone of about 50 miles (80 km), concerned primarily with ingestion of food and liquid contaminated by radioactivity.[31]

In 2010, the population within 50 miles (80 km) of the station was 254,049, an increase of 10.2 percent since 2000; the population within 10 miles (16 km) was 5,651, a 2.4 percent decrease. Cities within 50 miles include Lake Jackson (40 miles to the city center) and Bay City.[32]

Seismic risk

editThe Nuclear Regulatory Commission's estimate of the risk each year of an earthquake intense enough to cause core damage to the reactor at South Texas was 1 in 158,730, according to an NRC study published in August 2010.[33][34]

Reactor data

editThe South Texas Generating Station consists of two operational reactors. A two reactor expansion (Unit 3 and Unit 4) was planned but later cancelled.

| Reactor unit[35] | Reactor plant type | Capacity (MW) | Construction started | Electricity grid connection | Commercial operation | Current license expiration | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Net | Gross | ||||||

| South Texas-1 | Westinghouse 4-loop PWR | 1280 | 1354 | 22 December 1975 | 30 March 1988 | 25 August 1988 | 20 August 2047 |

| South Texas-2 | 11 April 1989 | 19 June 1989 | 15 December 2048 | ||||

| South Texas-3 (cancelled)[36] | ABWR | 1350 | 1400 | License terminated (2018)[37] | |||

| South Texas-4 (cancelled)[38] | |||||||

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ Johnston, Louis; Williamson, Samuel H. (2023). "What Was the U.S. GDP Then?". MeasuringWorth. Retrieved November 30, 2023. United States Gross Domestic Product deflator figures follow the MeasuringWorth series.

- ^ NextAxiom, A message from (2023-07-05). "U.S. nuclear capacity factors: Resiliency and new realities". American Nuclear Society -- ANS. Retrieved 2023-07-05.

- ^ "Reactor Details". PRIS. 1975-12-22. Retrieved 2023-07-05.

- ^ "Reactor Details". PRIS. 1975-12-22. Retrieved 2023-07-05.

- ^ Harman, Greg (24 October 2007). "CPS must die". San Antonio Current. Retrieved 14 August 2024.

- ^ 1634–1699: McCusker, J. J. (1997). How Much Is That in Real Money? A Historical Price Index for Use as a Deflator of Money Values in the Economy of the United States: Addenda et Corrigenda (PDF). American Antiquarian Society. 1700–1799: McCusker, J. J. (1992). How Much Is That in Real Money? A Historical Price Index for Use as a Deflator of Money Values in the Economy of the United States (PDF). American Antiquarian Society. 1800–present: Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis. "Consumer Price Index (estimate) 1800–". Retrieved February 29, 2024.

- ^ "General Municipal Election: November 17, 1973" City of Austin

- ^ "General Municipal Election: August 14, 1976" City of Austin

- ^ "General Municipal Election: January 20, 1979" City of Austin

- ^ "General Municipal Election: April 7, 1979" City of Austin

- ^ Power Reactor Information System of the IAEA: South Texas

- ^ Grieves, Robert T. (31 October 1983). "A $1.6 Billion Nuclear Fiasco". TIME. Retrieved 14 August 2024.

- ^ "General Municipal Election: November 3, 1981" City of Austin

- ^ "PRIS - Reactor Details". pris.iaea.org. Retrieved 2021-02-17.

- ^ "PRIS - Reactor Details". pris.iaea.org. Retrieved 2021-02-17.

- ^ a b "EPC Next Step In CPS Energy's Evaluation of Nuclear Option" CPS Energy

- ^ "NRG Files First Full Application for U.S. Reactor" Bloomberg.com

- ^ "$6.1 million spent to end nuclear deal" Express News CPS Energy STNP Expansion Termination Article

- ^ "TEPCO Partners in STP Expansion" STP Press Release

- ^ "CPS Energy sees need for new STP units". World Nuclear News. June 30, 2009. Retrieved 2009-06-28.

- ^ "Nuclear cost estimate rises by as much as $4 billion". October 28, 2009. Retrieved 2009-10-28.

- ^ "NRG ends project to build new nuclear reactors". The Dallas Morning New. April 19, 2011. Archived from the original on 2016-04-09. Retrieved 2015-03-14.

- ^ Matthew L. Wald (April 19, 2011). "NRG Abandons Project for 2 Reactors in Texas". New York Times.

- ^ "Licensing Board to Conduct Hearing Oct. 31 in Rockville, Md., on South Texas Nuclear Project New Nuclear Reactor Application" (PDF). US NRC Press Releases. US Federal Government. Retrieved 13 October 2011.

- ^ United States Nuclear Regulatory Commission. (October 29, 2013). "STP 3 & 4 Environmental Report-1.1.2.7 Proposed Dates for Major Activities". South Texas Project Units 3 & 4 COLA (Environmental Report), Rev. 10. Retrieved February 23, 2015. http://pbadupws.nrc.gov/docs/ML1331/ML13311B781.pdf

- ^ "Regulators approve new nuclear reactors near Houston". 10 February 2016.

- ^ feds-approve-new-nuclear-reactors-near-houston fuelfix.com,2016/02/09

- ^ "Electricity Data Browser". www.eia.gov. Retrieved 2023-01-07.

- ^ Kohn, Stephen Martin (2011). The Whistleblower's Handbook: A Step-by-Step Guide to Doing What's Right and Protecting Yourself. Guilford, CT: Globe Pequot Press. pp. 116–18. ISBN 9780762774791.

- ^ "About Us" South Texas Project Nuclear Operating Company

- ^ "Backgrounder on Emergency Preparedness at Nuclear Power Plants". Nuclear Regulatory Commission. Retrieved 2019-12-22.

- ^ "Nuclear neighbors: Population rises near US reactors". NBC News. 2011-04-14. Retrieved 2023-07-05.

- ^ "What are the odds? US nuke plants ranked by quake risk". NBC News. 2011-03-16. Retrieved 2024-08-16.

- ^ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2017-05-25. Retrieved 2011-04-19.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ Power Reactor Information System of the IAEA: „United States of America: Nuclear Power Reactors- Alphabetic“

- ^ Power Reactor Information System of the IAEA: „Nuclear Power Reactor Details – SOUTH TEXAS-3“

- ^ https://www.nrc.gov/reactors/new-reactors/col/south-texas-project.html Issued Combined Licenses for South Texas Project, Units 3 and 4 by the NRC

- ^ Power Reactor Information System of the IAEA: „Nuclear Power Reactor Details – SOUTH TEXAS-4“

Sources

edit- "Milestones". South Texas Project Nuclear Operating Company. Retrieved Jul. 14, 2005.

- "CenterPoint Energy Historical Timeline". CenterPoint Energy. Retrieved Jul. 14, 2005.